COYOTEWAY – Pages i-52

A Navajo Holyway Healing Ceremonial

Karl W. Luckert

and

Johnny C. Cooke,

Navajo Interpreter

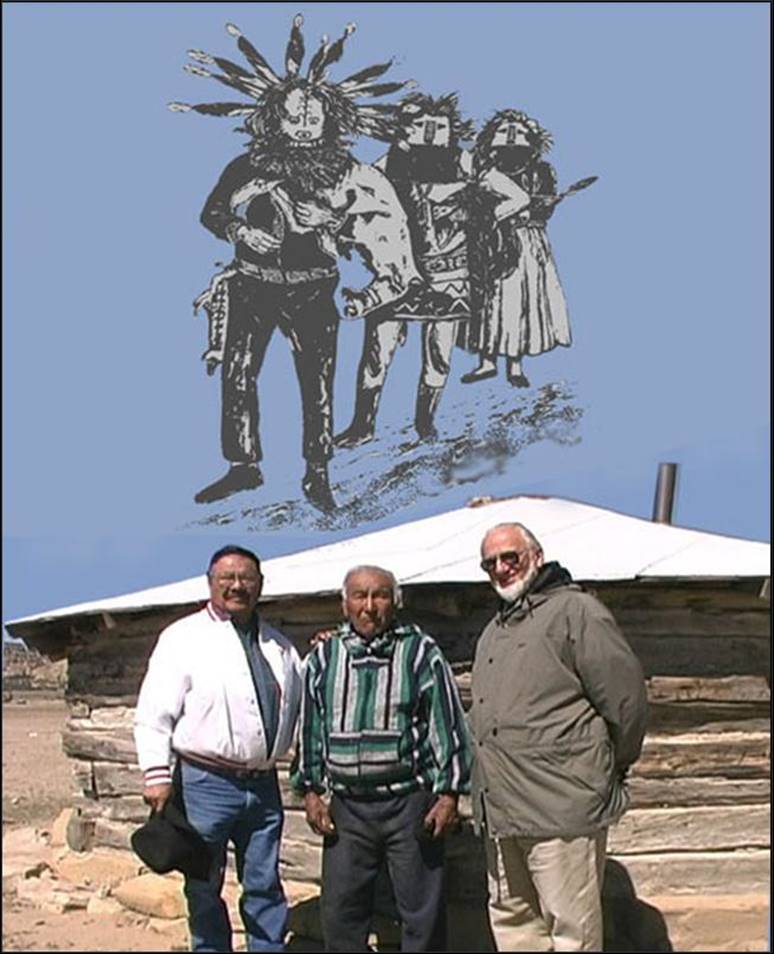

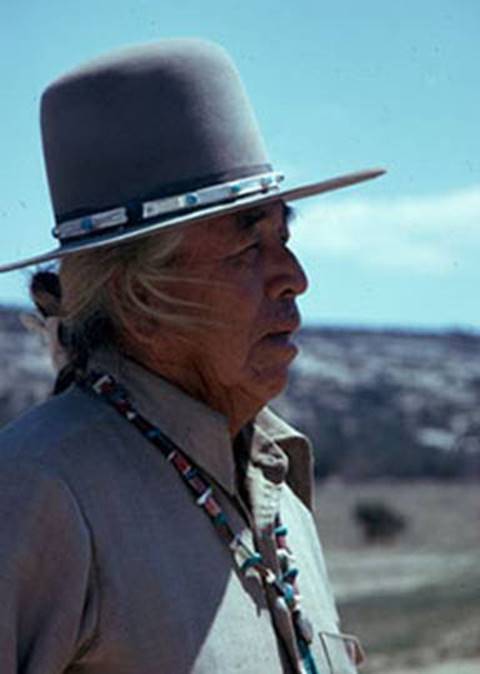

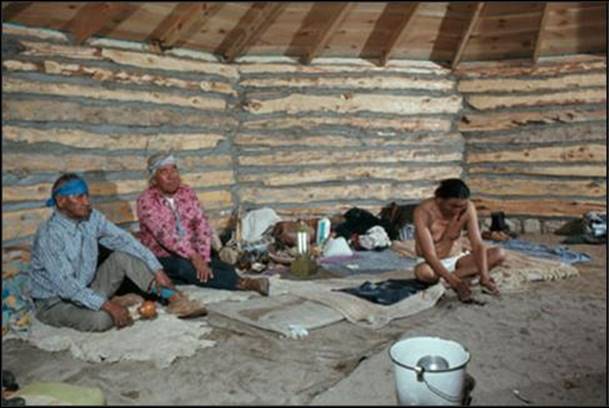

Johnny C. Cooke, his father Luke Cook at age 96, and Karl W.

Luckert, during autumn of 2000,

in front of the hogan where

Coyoteway was performed in 1974

Preface

PART ONE: THE CEREMONIAL AND ITS PRIESTS

1.

Introduction to Coyoteway 3-14

2.

Man With Palomino Horse and His Tradition 15-22

The Singer and His Teachers

The Mythico-historical Origin of

Coyoteway

PART TWO: COYOTEWAY PERFORMED

3.

The Nine-Night Sequence 25-30

4.

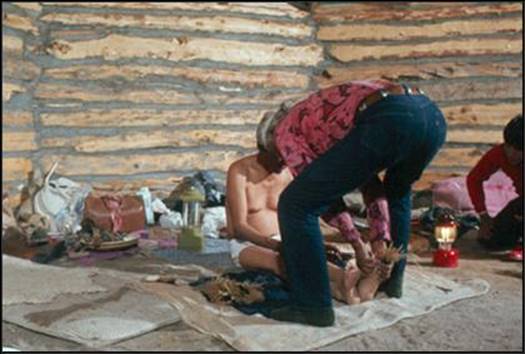

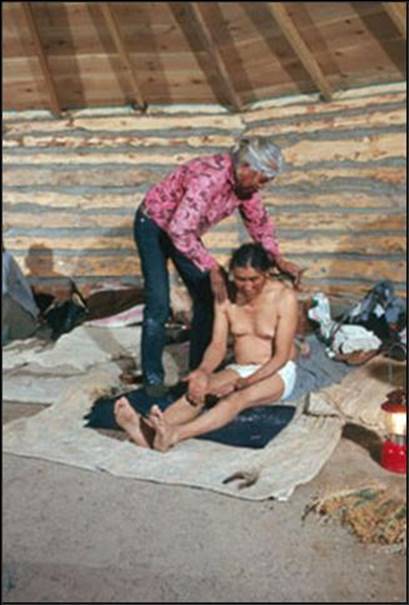

Unraveling Ceremonies 31-52

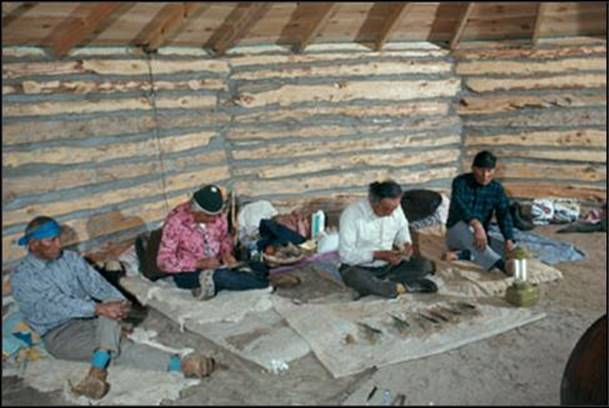

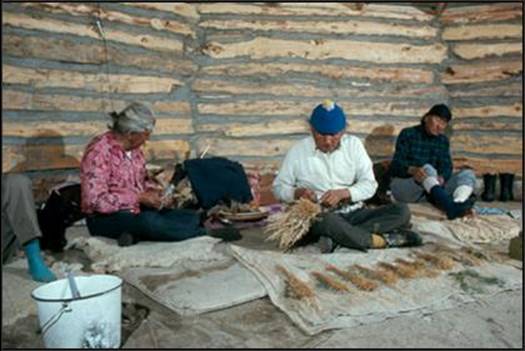

Preparations and Singing

Unraveling

Burning the Feathers

5.

Fire Ceremonies 53-96

Making New Fire

The Reed-prayerstick Bundle Rites

Preparations

Prayers

Delivery of

Reed-prayerstick Bundles

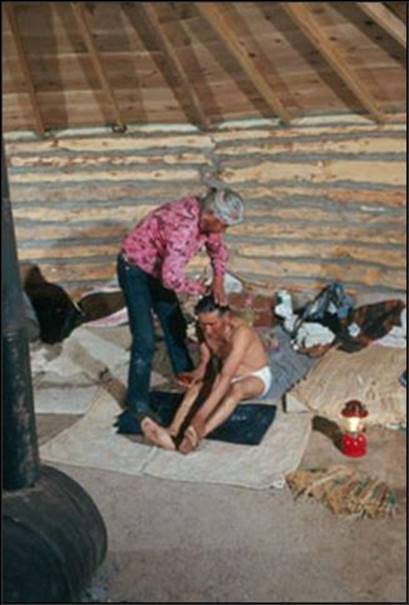

Sweating Rite

Preparations

and Sweating

Iiłkóóh Rubbing-on and

Drinking

Sprinkling Kétloh

Burning the Feathers

The Washing Rite

6.

Basket-Drum Ceremonies 97-120

Preparations and Aim

Fifth Evening

Sixth Evening

Seventh Evening

Eighth Evening Burning the Feathers

7.

Sandpainting Ceremonies 121-184

The Problem

of Naming the Yé'ii

The One-yé'ii

Ceremony

The

Sandpaintings

The Ceremony

The Three-yé'ii

Ceremony

The

Sandpainting

The Ceremony

8.

The Ninth-Night Summary 185-188

The following chapters are not included in this exhibit.

For Chapters 9 through 12 please consult the printed version.

PART THREE: EARLY RECORDS OF COYOTEWAY

9. Coyoteway Myth of

Yoo' Hataałii 191-202

10. Coyoteway Myth of Tséyi'

nii 203-216

11. Coyoteway

Myth of William Charlie 217-223

12.

Sandpainting Reproductions 224-233

Sandpaintings by Big Mustache

Sandpaintings and

Prayersticks by Bit'ahnii

Bidághaaí

Sandpaintings by William Charlie

Bibliography 235-239

Index 241-243

_________________________________

The Navajo Coyoteway ceremonial (mą'iijí hatáál) has lingered in the shadow of death more

than a century. As early as 1910 it has been declared extinct, in

an Ethnologic Dictionary by Franciscan scholars. Nevertheless, the

ceremonial has survived in the remote ravines of the conservative Black Mesa

area of northern Arizona, long enough for us to record and photograph a

complete nine-night version. This happened during January of 1974. After our

recording of this chantway, the last active Coyoteway singer,

Man-with-Palomino-Horse, has staged five more such complete nine-night

performances. Several years ago he died, and the Coyoteway tradition on the

Navajo Reservation died with him. Our book was published in 1979 under the

title Coyoteway, a Navajo Holyway Healing Ceremonial. A few years later this

book, too, has died mysteriously -- after its second printing.

As far as could be ascertained, the printing

establishment in Phoenix was sold and the new owners promptly destroyed the

plates. When the publishers decided not to invest in a reprint, the

copyrights reverted to Karl W. Luckert. Prodded by persistent inquiries

about the availability of this book, Luckert, in consultation with Johnny C.

Cooke, has undertaken to re-format the text for the Internet. The

photographs are now given in color -- something that was possible only for

ten images in the original book. Unfortunately, the orthography of a few

Navajo words has become flawed in the process. Several combinations of

Navajo diacritical marks are still not available on the Windows Word 2000

fonts -- and on the Netscape Browser the slashed letter "l" [ł] continues to

appear as question-mark. But this appears to be a small price to pay for

resurrection.

* * *

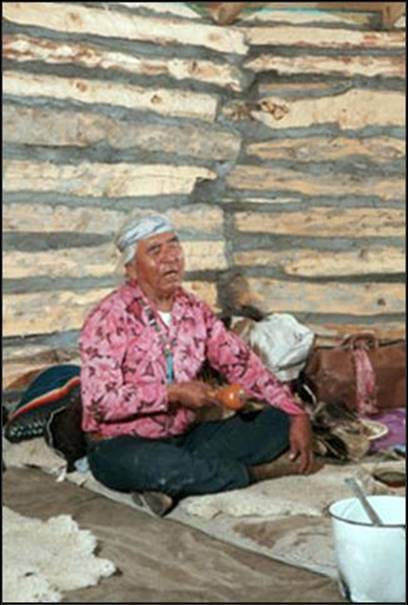

Three men, especially, deserve the gratitude of

writer, reader, and posterity; they are Johnny C. Cooke (John Cook), Luke

Cook, and Man With Palomino Horse. Johnny Cooke has been my faithful

interpreter through three major research projects. His superior command of

the Navajo language, and his open-minded religious sensitivity, together

were the key to success in both our negotiations and in the translation of

the materials. A sincere word of thanks is hereby also extended to his wife

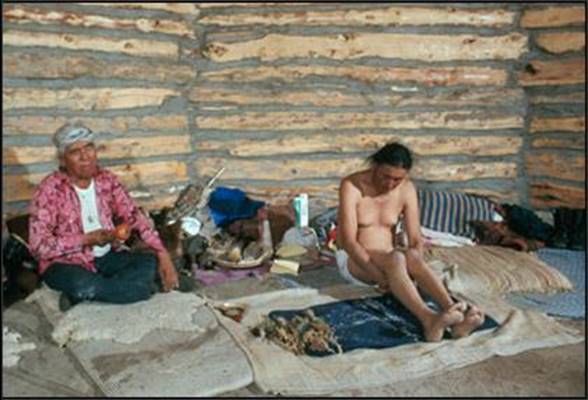

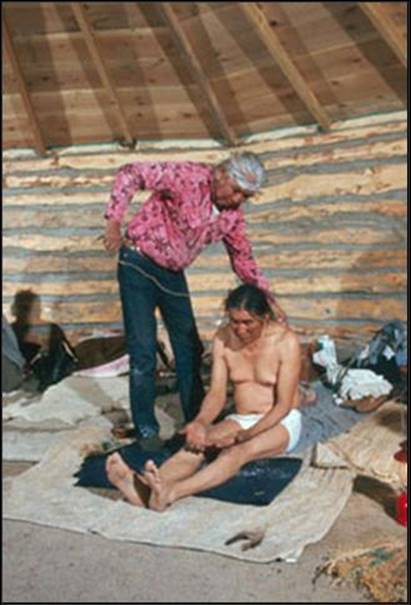

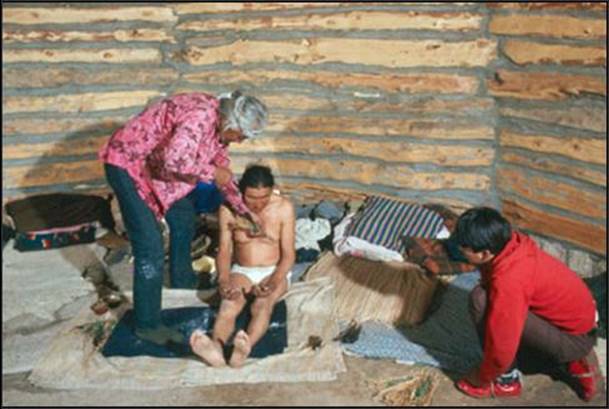

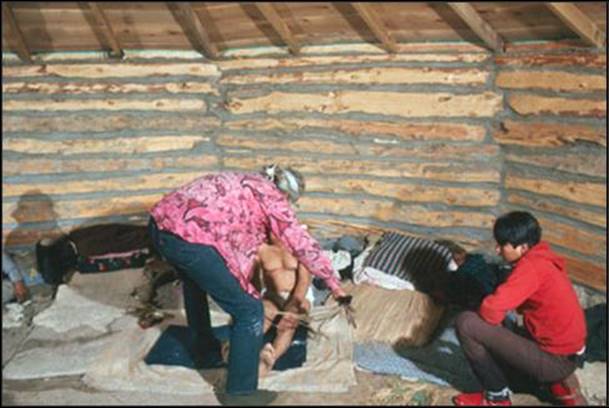

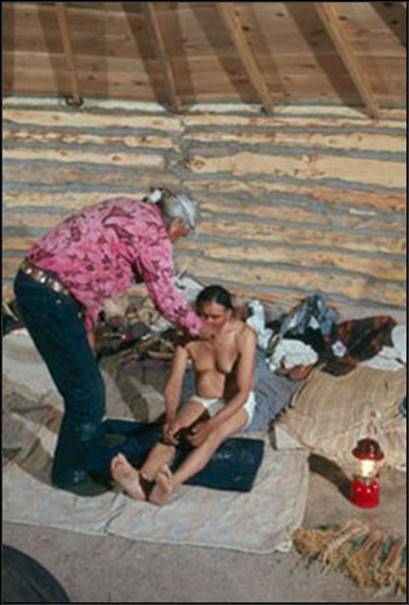

and children for enduring his frequent absences from home. Luke Cook has

been a devoted negotiator on our behalf, later also a very helpful

informant. He has selflessly volunteered to be our patient, and, seeing

himself in the traditional way still as the primary beneficiary, he has

insisted on bearing certain portions of the expenses himself. The consent of

his family, and the active support of his family, his relatives and friends,

is forever appreciated. Man With Palomino Horse, one of two surviving

singers of Coyoteway (mą'iijí

hatáál), has

consented to have his chantway recorded and preserved for posterity. Many

generations of Navajo students and world citizens will admire him for his

generous gesture toward a closed future. The world will never know the

struggle that went on behind his serene and dignified posture. Should

Coyoteway die ethnically pure, or should it be given to mankind? Some people

despair when they face the end of a road; Man With Palomino Horse dreamt a

broader vision.

A number of other people have helped me along the way. Melvin Nelson, of

Winslow, on many occasions during the negotiation stage, has saved me many

miles of extra driving by keeping our "pony express" relay communications

system going. When the ceremonial finally got off the ground, it was

my Northern Arizona University colleague. Bill Gillette, who let me use his

professional flash equipment to improve my photography. Then, in the days

after winter recess, when it appears to be difficult to grant leaves of

absence in Arizona, the Northern Arizona University administration

graciously gave me two additional days. Irvy W.

Goossen, another university colleague and

professor of Navajo, has helped me over and again with transcribing Navajo

words. His transcriptions correspond to the Young and Morgan orthography.

Barton Wright has discussed comparative Hopi materials with me, and the

library staff at the Museum of Northern Arizona has been as generous toward

me as always. Sam Gill, formerly a fellow student at

the University of Chicago, has through his work on Navajo prayer been a

stimulus for many an inspiration.

Before the manuscript was given to the University of Arizona Press, two

anthropologists with expertise in the Apachean field, Leland C. Wyman and

Morris E. Opler, together with a historian of

religions, Benjamin Ray, graciously consented to read it. The book owes many

improvements to their informed suggestions. It is difficult to estimate the

large debt that this author owes to the work of these and other scholars.

Without their generous assistance this publication would not have had a

chance to become what it now is. The many shortcomings which will

undoubtedly be found when I look at it ten years from now must not be

charged to the advice of others but to my own limited horizon.

While the greater portion of the expenses for this project has been paid by myself -- and suffered wonderingly by my family -- two partial grants-in-aid eventually came my way: one from the Smithsonian Institution and another from the Wenner-Gren Foundation. Then, in the summer of 1974, while working on the manuscript, I was given five weeks of support from Northern Arizona University. To all these institutions I express my sincerest appreciation.

Chapters 9 through 12 in this book (not included in this internet version) contain materials that have been archived in the Museum of Navaho Ceremonial Art, Inc., at Santa Fe. Director Bertha Dutton and Curator of Archives Caroline Olin have supplied me with manuscripts of unpublished Coyoteway myths; they have provided photo prints of eleven Coyoteway sand-paintings; and they have graciously mediated and granted permission to print. Maud Oakes has given permission to include her Coyoteway myth by William Charlie. Without the dedicated work done through time by people associated with this and other museums, we would all know less about Coyoteway than we now do.

After a number of years have passed over a printed report of this kind, attitudes and theories in the fields of history of religions and anthropology will undoubtedly have changed. One can expect that readers will want to question my materials in relation to my methods and procedures. Since personal ambitions and attitudes are inseparable from methodology, I have decided to provide readers with at least a hint of how Coyoteway was found and experienced by me. The possibility that such a statement will be judged as self-serving dwindles in the face of the greater likelihood that future readers, who have outgrown the mistakes of my generation, will on the basis of these disclosures find me quite inadequate. Yet, in fairness to Coyoteway and to future generations of students, I think that this risk should be taken.

My first knowledge about the presence of Coyoteway on the Navajo Reservation I owe to two scholars, Jerrold Levy, a professor of anthropology from Portland, Oregon, and Oswald Werner, a professor of linguistics from Evanston, Illinois. Both men were interested in recording as much as possible of the Coyoteway tradition. They were in touch with a Coyoteway singer somewhere on Black Mesa, though this happened not to be the singer with whom I eventually worked.

One year later, in the summer of 1971, I traveled into the field in search of materials related to the Navajo hunter tradition. Johnny Cooke, a Presbyterian theology student from Chinle, was my Navajo interpreter. During one of our numerous trips we visited Johnny's parental home at Black Mesa. We had come to put ear-markers on some steers and calves. After wrestling these animals, we offered to play tapes of a Navajo hunter myth to Luke Cook, Johnny's father.

That meeting marked the beginning of a developing friendship with the Cook family -- in time I became known there affectionately as Johnny's Grandfather. A comparison of Navajo and Israelite religion helped unexpectedly to build a bridge of understanding between the traditional father and his seemingly estranged Christian son. The Navajo Deerway myth (Luckert 1975) was easily grasped by both men as a pre-pastoralist, and thus a type of pre-Abrahamic, revelation of God Almighty. To both it became clear that the God, whom nobody has managed to describe accurately thus far, has revealed himself to Navajo hunter ancestors, among other manifestations, in the form of sacrificial Deer People. As a Lamb he seems to have shown himself to Hebrew shepherds, eventually also as an anthropomorphic savior. Luke Cook was quick to see that this same God could also have appeared as Coyote.

When father and son found similarities in these two traditions, it was definitely not the result of persuasion on my part. Rather, it was the kind of natural synthesis that rational people in all cultures have been making all along, especially when they were faced with having to live concurrently in two cultures. The fact that we all live in the same world necessitates that we share with one another our hypotheses and axioms. Moreover, in all my contacts with Navajo singers I have not met one who would have found it difficult to think of his gods collectively as a single supreme personage -- in terms of monotheism.

On that occasion Luke Cook told us about two Coyoteway singers who were still alive and able to perform. Both lived somewhere in the southern portion of Black Mesa. On later occasions I was told that some years earlier, Luke Cook himself had been an apprentice to a Coyoteway singer. By now his family had been converted to Christianity and he had ceased to help in the traditional ceremonials. A gradual change of attitude toward us could be observed when Luke Cook sensed his son's new interest in his traditional ways. This is why he gradually began to confide to us a few points of general information about the Coyoteway ceremonial. As an apprentice who had ceased helping in the ceremonials he did not feel authorized to give us specific songs, prayers, or stories.

In January 1973, Johnny Cooke and I drove to Black Mesa and found our Coyoteway singer, Man With Palomino Horse. Would he tell us the Coyoteway myth and sing the songs for us? His answer at first was no. But then, when Johnny introduced himself as the son of Luke Cook (chíshi biye'), the practitioner began to take us more seriously. All along he had been doubting our sincerity. His foremost concern now was that he was getting old and that he had no apprentice to carry on the Coyoteway tradition. No doubt this was an oblique reference to Luke Cook's terminated apprenticeship. We told him straightforwardly that as Christians we could not become his apprentices, but that we respected and would like to record his chantway in order to preserve it in a book for future generations. Perhaps someday in the future, after we have all gone the paths of our ancestors, young Navajo people would want to learn about this tradition. This took some thinking. At last, perhaps as a favor to Luke Cook, whom he still respected and who recently had referred a patient to him, the singer agreed to have us record the Coyoteway ceremonial. Nevertheless, Coyoteway information could not be discussed and Coyote songs could not be sung apart from an actual ceremonial. We needed a patient. As we left the singer that night he suggested to us, completely on his own, that for the ceremonial we should bring a camera -- there would be sandpaintings.

After midnight, through deep snow, we arrived at Luke Cook's house and told him about our meeting with Man With Palomino Horse. He was enthusiastic. Yes, the Coyoteway ceremonial should be saved from complete extinction -- if not by an apprentice, then at least in a book. He volunteered to discuss our plans with a prospective patient he knew and to make the arrangements for us. He would then ride on horseback to the nearest telephone.

In March 1973, while doing work at the University of Oklahoma, I drove again into Navajoland to investigate. Johnny had, meanwhile, become the minister of the mission at Indian Wells; I found him there. The news he had was discouraging indeed: the shepherds around Black Mesa had suffered extensive livestock losses because of the heavy snow, and our prospective patient had died without having the benefit of a Coyoteway ceremonial. That night I fled a traffic-choking blizzard over northern Arizona and drove into the valley of Tucson; I was forced to return to Oklahoma by way of Texas.

In May we made another attempt to reach the singer. This time Luke Cook accompanied us. The proposed brief visit with the singer turned into a daylong search, one hundred miles over roads that were not roads. Our clutch gave out and had to be mended temporarily, in the midst of a sandstorm. I had to agree with my Navajo friends, that "chasing a coyote is not easy." In the evening we found our man at his home. I had to agree again. "Coyote is tricky!" But if Coyote is a trickster, he also has a human heart. Our daylong ordeal of trying to find the singer convinced him of our earnest determination. It, in part, atoned the practitioner's former apprentice for not completing his apprenticeship.

At that meeting I was given a choice: either to record five nights of Coyoteway in about a week in the home of one of the singer's relatives, or to wait until a full nine-night ceremonial could be arranged. This was a difficult choice. Should I opt for the first half of the ceremonial, would I ever get the remainder? The second portion is performed only over persons who have had the first part. If I chose to wait, would a patient ever be found who needed the full nine nights? Would the singer live long enough? I decided to wait until a full nine-night performance could be arranged.

This decision became considerably easier to live with when Luke Cook disclosed some of his thoughts to me. There was an uncle, who, like himself, a former apprentice, was also eligible to have the full nine-night ceremonial performed over him as an initiatory procedure. This idea immediately appealed to me. The chance for having a full ceremonial is far greater with a patient who is to be initiated as a singer. Such a person needs the full ceremonial for his full authorization; on the other hand, if the ceremonial is performed over a patient with actual symptoms of Coyote illness, and if in the process the symptoms get worse, the performance has to stop.

My choice was rewarded with Luke Cook's further suggestion: "If this uncle will not be our patient, I myself will be it." I was elated. Now it could only be a matter of time. No ceremonial could be sponsored by the Cook family right then for two reasons. A grandmother was about to die; if that should happen the ceremony would have to stop a full month. Then, they all had suffered far too heavy livestock losses in this winter's snow. The material means for such a ceremonial were not available. As it turned out, the uncle was willing, but his family vetoed his plans for having his initiation ceremonial. It was now Luke Cook's turn to become our patient.

The final arrangements for the ceremonial required eight more months. Luke Cook decided that he should build a new hogan for the occasion. Then, we attempted to arrange a leave of absence for Johnny from his congregation. Soon it became apparent that Christ and Coyote are divine savior manifestations from widely separate culture strata. Savior figures from the hunting era and from a monarchal civilization are not as easily reconciled as some well-meaning historian of religions might think. After six more negotiation journeys to the reservation it was agreed that I would do the recording alone, and that Johnny would be free to translate from the tapes.

On the morning of January 3, 1974, the coldest and snowiest day of winter, I loaded several boxes of equipment into my vehicle and drove to Black Mesa. Beautiful snow, which at many places lay two feet deep, had to be driven through with four-wheel-drive gear, snow tires, chains, a "sheepherder's" jack, and a shovel. A severe cold began to affect me from the beginning. Three bottles of cough syrup and one bottle of antibiotics later, on January 12, I drove home. What I had experienced in these ten days belongs among the most cherished memories of my professional life. The Coyoteway ceremonial which required one year of final negotiations, five months of preparations, 15,000 miles of driving and other things, is saved from oblivion.

A few years later (in 1979), as the manuscript approaches final preparation for becoming a book, a postscript to this Preface seems called for. Our patient, Luke Cook, participated earnestly as if he were to become a Coyote-priest. His participation in the Coyote ceremonial, however, was a farewell gesture to a tradition which he still respects, but which he nevertheless decided to abandon. He knows that because of his quitting the Coyote ceremonial will become extinct in a few years. In view of this fate, he volunteered and enthusiastically cooperated in the recording procedures. The temporarily initiated Coyote-priest continues nevertheless to move closer toward Christianity.

Sentiments of lament, bordering occasionally even on hostility toward

representatives of intruding religions, have been expressed by some

scientific field researchers and historians of religions. Their fields have

been altered before their eyes and have disappeared. And yet, life still is

motion; it seldom stays fixed long enough for scientific verification. Even

students of eternal things must learn to adjust to life's onward flow and

learn to celebrate its passing moments. Our Coyoteway

heir has as much right as any human being to follow the brightest star that

he happens to see. For him Coyote has now trotted into the shadows to hide.

And for the historical record it must be said that, at this point in time,

his guiding light and divine tutelary is Christ. (1) The

process of divine revelation does not stop just because a Coyote hides in

the bushes.

K.W.L. 1979

updated for the Internet 2000

________________________________

(1) PostScript: Two weeks after the ceremony, Luke Cook loaded two

sheep on the back of his pickup truck, for a church picnic. He was ready to

join a nearby Christian church. As it turned out, the performance and

recording of the Coyoteway ceremonial has

facilitated for Luke Cook an honorable transition, to rejoin his family that

had converted earlier.

__________________________________________________

Copyright information for the out-of-print book:

THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA PRESS & THE MUSEUM OF NORTHERN ARIZONA

CO-PUBLISHERS

Copyright for both agencies 1979

The Arizona Board of Regents (for the Press) & the Museum of Northern

Arizona

All Rights Reserved

Manufactured in the U .S .A.

Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data

Luckert, Karl W. 1934-

Coyoteway.

Bibliography: p.

includes index.

1. Navaho Indians -- Rites and ceremonies. 2. Navaho Indians --

Medicine. 3. Indians of North America -- Southwest,

New -- Rites and ceremonies.

4. Indians of North America -- Southwest, New -- Medicine. I. Title.

E99.N3L8 1978 392 78-10358

ISBN 0-8165-0670-1

ISBN 0-8165-0655-8 pbk.

[After the printing plates had been accidentally destroyed, the University

of Arizona Press transferred the copyrights

back to the author, Karl W. Luckert]

____________________________________________

1

Introduction to Coyoteway

Navajo religion consists of twenty or more overlapping but nevertheless

distinct ceremonial traditions. In the opinion of this writer these

traditions are traceable in mythology, by way of geographized ecstatic

journeys (vision quests), to their respective shamanic founder or founders.

They are traceable in history, possibly, to a point in time when several

formerly shamanic traditions became amalgamated into the conglomerate

healing ceremonials of later priestly hataałii or

"singers." Since my general views on Navajo religious history have recently

been published (Luckert 1975), this statement on

the subject of historical development is brief.

The arrival of the first Navajo-Apachean hunters in the Southwest, from the

north, is commonly estimated at about A.D. 1500. In the sixteenth and

seventeenth centuries most of the healing rituals of the Navajo-Apacheans

were probably still securely anchored in hunter ideology. But after coming

to the Southwest, and after a change in life-style, their hunting and their

hunting rites became less important. At the same time, the direct concern

for health in ceremonialism remained. In dialogue and in competition with

representatives of Pueblo Indian maize-planter cultures, the Navajo-Apachean

hunter shaman, with his northern Athapascan heritage, has gradually adapted

to become a sort of learned professional -- a priestly performer of

composite song-ceremonials, thus a "singer."

Pueblo Indian cosmology, the worldview that has been taking shape in the

Southwest for about two thousand years, appears to be in

Page 4

its basic outline a product of the great archaic civilization of Middle

America (see Luckert 1976). Its basic notions

are explained in terms of prehuman events in the

myth of emergence. For instance, according to Hopi tradition, the mythic

evolutionary emergence of the people from the underworld is generally

divided into four stages. The "fourth world" of present-day earth-surface

people is again structured numerically in relation to four cardinal points.

Specialized gods preside over each of the four directions.

Confronted by this tightly structured view of a planter people's

universe, the early Navajo-Apachean shaman found himself groping for answers

which would relate his divine hunter tutelaries

to the directionally stationed gods of the Southwest. For the traditionally

individualistic shaman it was no longer sufficient to encounter one divine

guardian at a time, or to get initiated by a predecessor into a close

relationship with that divine guardian. Confronted by Pueblo Indian

systematic cosmology he needed the combined strength of his Athapascan

heritage to achieve a synthesis that would fall short of total surrender.

And so it seems that Navajo narrators of myths began to draw increasingly

from a larger number of available shamanic formulations. As scholastic

syntheses, the originally shamanic bodies of knowledge ceased to be

shamanic. Instantaneous communication with divine

tutelaries was replaced increasingly by systematic learning and

poetic creativity. The credit for all this creativity was, nevertheless,

given to the gods, in a posture of religious humility.

While Navajo singer apprentices learned the traditions of several

shamanic masters, the divine guardians of the latter assembled above them

into some sort of corresponding pantheon. The result is that Navajo

ceremonial traditions feature now overlapping but, nevertheless, different

pantheons. And, in accordance with the four-directional scheme of Pueblo

Indian cosmology, some freely roaming tutelaries

of the Navajo-Apachean hunters were stationed permanently. Learned Apachean

hunter lore could thus be harmonized with the priestly concepts of Pueblo

Indian cosmology and anthropogony. The arrangement that has the Talking-god (haashch'ééłti'í) in

the east, Calling-god (haashch'éoghan) in

the south, Begochidi in the west, and Black-god (haashch'ééshzhini) in

the north, appears to be the most popular synthesis in the Black Mesa area.

Other traditions list Calling-god as a "Talking-god in the west." Still

other arrangements have a Talking-god stationed in each of the four

directions, or as four divine persons in the east, or everywhere. From a

historical perspective it seems that Talking-god, as an anthropomorphic

"talker," associated predominantly with the White East, has risen to highest

prominence.

Page 5

This era of general synthesis and poetic creativity in the history of

Navajo religion seems, in all likelihood, to have been precipitated by the

Pueblo Revolt of 1680. Large numbers of Pueblo Indians fled from along

the Rio Grande when the Spanish retaliated. Many of them were absorbed by

the Navajo tribe. The stories of shamanic vision quests, brought from the

north and now challenged by Pueblo cosmology and ceremonialism, were retold

by fascinated newcomers in the hauntingly bright and magnificent landscape

of the Southwest. All this together, in the course of a few centuries,

produced a ceremonial ferment that is unequalled anywhere in North America.

The challenge that is put on the priest and the mythmaker is great indeed in

the Southwest, because world-sketches of heroes and gods must excel those

attainable by ordinary Earth-surface people. The general pattern of this

Apachean-Pueblo synthesis is still very much in evidence in the form and

content (i.e., first half versus second half) of the

Coyoteway ceremonial. Specifically, in this instance, this synthesis

may be as recent as the early part of the nineteenth century.

According

to Leland C. Wyman (1970b, p. 3), there were formerly "about twenty-three

Holyway chantway systems,

all for curing illnesses, to which -- by elaboration according to male and

female branches, ritual, and other considerations -- about forty names for

song ceremonials could be ascribed." Wyman's newest, at the moment

__________________________________________________________________________________________

The Holyway Chantways

Shooting Chant subgroup

Hailway

* Waterway * Shootingway Red

Antway Big Starway Flintway

(?)

Mountain Chant subgroup

Mountainway Beautyway Excessway

* Mothway *

God-Impersonators subgroup

Nightway Big

Codway * Plumeway Coyoteway

* Dogway * Ravenway

*

Wind Chant subgroup

Navajo Windway Chiricahua Windway

Hand-Trembling Chant subgroup

Hand-Tremblingway

Eagle Trapping subgroup

Eagleway

* Beadway *

Extinct ceremonials of uncertain affiliation

Awlway

* Earthway * Reared-in-Earthway

(?) *

* extinct, obsolescent, or virtually obsolescent. (?) indicates questionable

classification.

Page

6

still unpublished, chart of these chantway

systems is included here with his permission. Coyoteway

is classified as a chantway of the

God-Impersonators subgroup and as "virtually obsolescent."

Classification of Navajo chantways is

made difficult by the fact that two somewhat independent criteria are being

used interchangeably -- modes of performance and etiological factors.

Coyoteway is readily, and for obvious reasons,

assigned to the God-Impersonators subgroup. God-impersonators do indeed

appear during performance of this ceremonial. Nevertheless, based on Navajo

etiological reasoning, a good case can be made for having

Coyoteway in the Mountain Chant subgroup

alongside ajiłee, the so-called

Excessway.

Recent research in the ajiłee tradition

has revealed that, rooted in the hunter tradition,

Coyoteway and ajiłee are indeed

closely related. A more extensive discussion of the ajiłee-mą'iijí dichotomy

will have to be postponed to a forthcoming publication. Let it suffice to

say here, that Luke Cook, our Coyoteway patient,

has traced all illness among humankind to the great Coyote beyond the east.

From there illness is conveyed to us by Sun and Moon. According to its more

specific etiology. Coyote illness is mediated from Sun and Moon to humankind

by predators. "It is gotten when members of the Coyote family (which in a

broad sense includes all predators) put their heads together and decide to

get to you." Ajiłee is basically the same

kind of illness. It, too, is sent into our world by the great Coyote who

lives beyond the homes of Sun and Moon in the east. It, too, is conveyed

into our world by these celestial personages. But in contrast to what is

specifically referred to as Coyote illness, ajiłee is

passed on to humans when they eat the meat of the game animals without the

proper counter measures; it has gotten into the game animals when, in

self-defense, they ate certain poisonous or hallucinogenic plants; such

plants have, in turn, received ajiłee power

from having been made pregnant by Sun and Moon.

Regardless of the subgroup to which it belongs,

Coyoteway is a healing ceremonial of the Holyway

type. This means, it seeks to remedy the patient's estrangement from the

Holy People and his provocations toward them.(1) Angered gods, in

this instance angered Coyote People, inflict their brand of illness on the

human offender. Subsequently, the divine cause and his human victim must be

reconciled ceremonially with songs and prayers; the evil residues of

illness must, nevertheless, be exorcised, in Evilway

or Weaponway fashion, with the appropriate

rites. Each species of Holy People, such as Bear,

________________________________

(1) Evidence of an Evilway version of

Coyoteway is presented below, in Chapters 11 and

12, with the myth and the sandpaintings of

William Charlie. See also an explanation of Evilway

modes of performance later in this chapter.

Page 7

Snake, Wind, or Lightning, requires its own special reconciliation

procedures. So it may be said, that each of the twenty or more chant-ways

represents a sort of "mini-religion." Each of these small-scale religious

traditions has its own distinct soteriology; it saves the devotee, that is,

the patient, from his particular predicament and estrangement, yes, even

from his self-destructive open rebellion against a divine being. The process

of liberation and recovery requires usually a two, five, or nine-night

performance of the god's (or gods') own prescribed reconciliation

ceremonial.

Adjusted to Pueblo Indian cosmography, the divine Coyote People live

underground. At the same time, manifestations of these divine prototypes

roam in the surface world as animals. Mą'ii is

the Navajo name for Coyote; it is also a generic name for the larger wolf

and the smaller foxes. The remaining predators, even snakes, are sometimes

included in the extended ma'ii family.(2) The

Coyoteway which is presented here does not

include any references to wolves, but according to our informants it

includes all the Coyote People who now live in the Navajo territory: White

Coyote in the east, Blue Coyote in the south, Yellow Coyote in the west, and

Black Coyote in the north. Of these the Yellow Coyote (yellow or red fox)

and the Blue Coyote (gray or silver fox) are native in the Black Mesa area.

Black Coyote is said to live "somewhere on the Navajo Reservation; he is

used in the yé'iibicheii (Nightway)

ceremonial" (Luke Cook). Specifically, it is the Gray or Blue Coyote from

the south that figures in the last sand-painting ceremony where a

yé'ii-impersonator carries a stuffed specimen of

the mą'ii species. In the

sandpainting itself, animal-shaped and

anthropomorphic Coyote People of all four colors are represented.

For diagnostic purposes the Navajo Coyoteway

can be performed as a two-night ceremonial. If it proves effective, a

continuation of up to at least five nights is called for, namely, the first

four nights (evenings and mornings) of the complete nine-night sequence and

a basket-drum summary on the fifth night. The second four-night portion of

the full sequence can be considered as a separate ceremony. For historical

interpretation, someday, it will be significant to know that the Holiness

Rite of the Jicarilla Apache corresponds to the second half of Navajo

nine-night ceremonials. The first portion of the Navajo sequence is omitted

in the Jicarilla ceremonials (cf. Opler 1943,

pp. 94f). Nevertheless, on account of this I do not regard the first four

nights of Coyoteway as constituting a later

development. On the contrary, the rites on the first four evenings and

mornings strike me as

___________________________

(2) Mą'i is an old Apachean form for "animal."

See, for instance the Chiricahua mbai

-- coyote; mhai'tso -- wolf; mba'ishói

-- lizard. (Personal communication of Morris E.

Opler.)

Page 8

being, in the Navajo historical context, much more archaic than the

Puebloized sandpainting

rites which follow. A combination of at least two basically different

ceremonial traditions seems, therefore, indicated. In the case of the Navajo

Coyoteway the synthesis of two such traditions

is indeed firm. While the four-night portions of the ceremonial are

separable, patients become eligible for the second portion only after having

experienced the first portion earlier.

In contrast to Luke Cook, whose Coyote theology of cosmic dimensions

has already been introduced, our Coyoteway

singer, Man With Palomino Horse, insists on a simpler explanation -- that

Coyote illness results only from offending animal Coyote persons. According

to him, prior to 1948, or thereabouts, a bounty was paid on the Navajo

Reservation for coyote skins. Apparently this was a government effort at

reducing the ever-increasing livestock losses, especially among young lambs.

But this well-intentioned measure burdened the coyote-hunting shepherds with

divinely caused troubles and with human guilt. Not many centuries ago the

Navajo people were hunters. Coyote was a fellow hunter who probably enjoyed

the rights of kinship that then applied to all fellow hunter peoples. As the

explanations to some of William Charlie's sandpaintings

(Chapter 12) seem to indicate, Coyote functioned occasionally, though

definitely more seldom than his big brother Wolf, as a divine tutelary power

in hunting.

Still in the 1880s Coyote was regarded as a respectable hunter

tutelary among the Zuni Indians. Frank H. Cushing (1920, pp. 414-515) has

recorded a mythological narrative about a hunter whose divine sponsor and

guardian was a Coyote person. It seems at least possible that the portion of

the Zuni story, which refers directly to the Hunter/Coyote relationship, has

had parallels in other hunter traditions of the Southwest. Numerous

incidents from Navajo coyote mythology can be traced to Pueblo Indian

traditions. Moreover, William Charlie's Navajo

Coyoteway could be performed for success in hunting.

In any case, later, when the Navajo hunters had become herdsmen

provisioned with and equipped by Western materialism, they were hunting

coyotes as nuisances and pests. This all too sudden change to a pursuit of

new values took its toll. Coyote illness soon was on the increase and was

persistently diagnosed in the Black Mesa area. Since 1948, according to our

practitioner, Coyote troubles have been declining steadily in this area.

The manner in which Coyote illness is caught was explained by our

singer in the following manner: When a Coyote person is shot and left to

die, his last spasms and twitchings, as they

suddenly cease in the animal person, leap onto the killer. This happens most

easily if some-

Page

9

how in the process of killing the hunter has eye-contact with his victim --

Coyote continues to recognize and to haunt the offender. But this can also

happen through physical contact with the animal's dead body or even with the

decayed remains of a Coyote person. And in this regard no shepherd who

strolls through the sagebrush pastures can ever be sure of his personal

immunity. Killing a Coyote person means offending him. The symptoms of the

animal's suffering which are thrown onto the offender continue as a sort of

nervous malfunction, as a shaking of the head, hands, or of the entire body.

Coyote illness may also be indicated by a twisted mouth, by

cross-eyed vision, by weakened eyesight, loss of memory or loss of mind,

and by fainting (Luke Cook). Earlier sources (Franciscan Fathers 1910, p.

363) counted mania and prostitution (sex frenzy) among the symptoms of

Coyote illness. Wyman and Kluckhohn (1938, p.

27, informant "R") named prostitution, mania and rabies. Their informant

"M" added sore throat and stomach trouble. Recently I have even been told of

a case where chronic alcoholism was diagnosed as Coyote illness.

Notwithstanding possible later embellishments, mania, nervous malfunctions,

and rabies seem to comprise the basic symptom pattern of Coyote illness most

naturally. What our practitioner has described as shaking and twitching may

well be traceable to rabies. This seems even more likely if we consider that

our patient, after he is initiated into a sort of kinship with Coyote

peoples, must also respect dogs, wild cats, badgers, porcupines, and skunks

-- all potential carriers of rabies.

Nevertheless, these considerations do not allow us to simply reduce

the Coyoteway healing procedure to a primitive

attempt to cure rabies. No scientific experiment has yet disproved the link

between rabies and the intentions of some divine Coyote peoples -- not to

mention the intentions of the cosmic Coyote who transmits his spells on

humankind from beyond Sun and Moon in the east. First and foremost, in the

perspective of the Coyoteway tradition is the

wrath of divine Coyote people, and it must be placated.

Meanwhile, for the majority of the Navajo people Coyote has lost his

positive value and function. Some people on the reservation barely seem to

know anymore that the shakedowns (the dust or "pollen" brushed from a coyote

being) contain power to procure wealth. Most people have by now come to

interpret the sighting of a coyote as a bad omen. Like many things that

still had their proper place in the old Navajo hunter tradition, and like

his big brother Wolf, Coyote has come to be associated with witchcraft.

This defamation of Coyote as a divine person appears to be the result

of two parallel developments. The first is that all hunter gods

Page

10

eventually do suffer defamation if their human protégés cease to be hunters

and if they learn to answer to different types of gods (cf.

Luckert 1975, pp. 186-90). Coyote is a trickster

person par excellence. Among archaic hunters this reputation gave him

prestige; hunters daily tried to imitate his trickery.(3) But

trickster gods among presiding shepherds or among sedentary planters are a

nuisance -- their archaic behavior burdens them soon with the reputation of

being wizards or even of being devils. In spite of all this, Coyote does

nothing to redeem his reputation -- he kills the shepherds' lambs. According

to what seems to belong to the Pueblo Indian portion of Coyote mythology,

this trickster also steals the farmers' maize.

There is a second reason for Coyote's bad reputation. Aside from

suffering the universal fate of all hunter gods in post-hunting cultures,

Coyote, while getting involved in medicinal ceremonialism, came under

suspicion precisely from that direction. Luke Cook, our patient, traces

every kind of illness to the great Coyote beyond Sun and Moon in the east;

and as far as Coyote's general disposition can be understood -- "Coyote

giveth and Coyote taketh away." So it seems that the present defamation of

Coyote is being generated also by that same general concern which

necessitates various versions of Evilway healing

ceremonials.(4) Evilway performances

emphasize exorcism and are held primarily to drive away vengeful ghosts,

their bewitching influence, together with evil hosts of other witchcraft

elements. Evilway ceremonials today run a close

second in popularity to the Blessingway rites.

Their popularity, it seems, runs parallel with the general fear of

ghost-influence in Navajo society. Fears of various kinds marry each other

easily.(5) In any case, it must be noted, that the deezlájí (Weapon-

or

____________________________

(3)Apache tribes used Coyote ceremonies for trickery of war (personal

communication of Morris E. Opler). On the other

hand, it was insisted on by the participants, that sexual trickery, which is

frequently attributed to Coyote, has nothing to do with the performance of

the Coyoteway ceremonial that is recorded in

this book.

(4)Evilway rites became increasingly

necessary during the Fort Sumner period (see Chapter 2). Also in Chapter 2,

note 2, Coyote's involvement in Pueblo Indian witchcraft is documented.

(5)I have delineated my incomplete views on this subject in The

Navafo Hunter Tradition (pp. 199-202). The

increase in the fear of ghost-influence, in Navajo history, appears to have

been primarily the result of having lost touch with the traditional "Black

Earth" eschatology. According to an informant of Wyman, Hill, and

Osanai (1942, pp. 34-37), the dead Navajo people

formerly went to join their predecessors who had returned to Black Earth, a

northern place. It seems that upon moving south, in confrontation with

Pueblo Indian emergence mythology, and with an ever growing dedication of

practitioners to retain their patients' health at any cost, apparitions of

the dead ceased to be tolerable signals for rejoining the ancestors. For

people who refuse to be escorted away -- at least "not yet" -- ghost

apparitions are bad omens. For people who no longer know where to go after

death they are evil in general and a threat to human existence.

Morris E. Opler (personal communication)

suggested that defeat, loss of territory in the face of a growing

population, lack of resources, high incidence of disease, alcoholism, etc.,

cause friction and suspicion among Navajos; further, that these human

conflicts, the ill will and suspicions which they engender, play a large

part in the perpetuation of the fear of ghosts and witches. This statement

does indeed explain the intensification of fears in certain culture areas.

But it also appears that religious eschatologies

do not necessarily obey the laws of economics, anatomy, or psychology. The

same troubles that in one place intensify interpersonal conflicts and

subsequent fears, are resolved elsewhere by the vision of a real afterworld

in favor of a harmonious coexistence with the dead. Proof of this has been

the Ghost Dance religion toward the end of the nineteenth century on

the Great Plains. And, while tear of witches appears to linger today in the

Navajo Peyote religion, frequent anticipation of "a new heaven and a new

earth" has generally transformed fear of the dead into a relationship of

friendship with them.

Page 11

Fightingway)

attitude which is expressed in Evilway rites

against certain causes of disease -- whether they be ghosts, witches, or

defamed archaic gods -- is the opposite of the search for reconciliation

which predominates during Holyway rites. And

having been caught in this general trend of Evilway

thinking, Coyote has become associated with the "wrong kind of people."

In several versions of Evilway mythology

-- as in Upwardreaching-way and in the myth of

Ghostway in the Male Branch of

Shootingway -- Coyote is no longer mentioned in

Holyway fashion as an offended deity, a

subsequent patient, or as a reconciling agent of health; instead, he is

regarded exclusively as a cause of illness. In this manner Coyote has become

identified with vengeful ghosts and with evil witchcraft elements with whom

reconciliation is no longer possible. Coyote, the already defamed hunter

tutelary roaming among shepherds, must now be driven away -- exorcised in

order to safeguard human health. And so it seems that, because of an

increase in Evilway-type thinking, this

Holyway-type ceremonial was increasingly

misunderstood and avoided. Had it not been for the government's bounty on

coyote skins, which produced a flare-up of Coyote illness and a demand for

the ceremonial in the conservative Black Mesa area, the

Coyoteway ceremonial of the Holyway type

would probably not have survived. But now, after several decades of inroads

made by American secular education, it seems as though this religious

ceremonial is definitely doomed.

While his ceremonial is disappearing, Coyote as an archaic divine

figure is still a long way from dying. Indeed, he was forced into joining

the ranks of antiquated and defamed hunter gods, but Coyote mythology

itself credits him with several resurrections. His positive role is still

vaguely reflected in the ethicized fables that depict the great Coyote of

Coyoteway as a laughable villain, buffoon, or

bungler -- more often than as a shrewd exemplary model for hunter

tricksters. The archaic Coyote, the epitome of hunter tricksters, could

indeed be a clownish bungler. Divine incarnations among hunters need this

sign of humanity. On the other hand, the Coyote of

Coyoteway is also a greater-than-human personage, a deity who, when

angered, inflicts his brand of punishment or illness and who, when

reconciled with the use of his own prayers, songs, and rites, restores the

patient to health. He even helps a man to gain prosperity.

Page 12

The strongly ethicized, popular Coyote tales that until now have been

available in ethnological literature represent, as all ethical systems do,

only the tail end or afterglow of a religious fascination. The real

Coyoteway ceremonial has been classified as

"extinct" by the Franciscan Fathers in 1910 (p. 392). From the perspective

of a historian of religions it seems therefore extremely fortunate that the

archaic core of Coyote religion among the Navajo, the "head of the comet,"

so to speak, could once more be sighted and seen in a meaningful historical

context.

* * *

A brief explanation about nomenclature may be in order at this point.

A Navajo healing ceremonial is called a hatáál, a

"sing." The person who officiates is a hatááłi, a

"singer." However, almost everywhere in the Western world the word "singer"

conjures up some associations with operas and folk music. In my earlier work

on the Navajo hunter tradition I have used, with some hesitation, the

popular term "medicine man." Leland Wyman has advised strongly against using

this term in connection with Coyoteway.

"Medicine man" reminds him of America's once popular medicine shows.

Obviously, Navajo healing ceremonies should not be confused with

unscrupulous salesmanship and with a circus atmosphere. Wyman, who is also a

scholar of biology and physiology, suggests that the term "practitioner" be

used.

As far as the title "shaman" is concerned, I am still very

sympathetic toward Mircea Eliade's delineation

of shamanism as "techniques of ecstasy." At the same time, I see that

outside the Tungusic-Siberian realm shamanism is

not always clearly definable in terms of ecstasy. In the American Indian

area a rational discourse with the god(s) often takes the place of ecstasy.

Moreover, individuals who would be better classified as priests sometimes

have ecstatic experiences. Morris Opler suggests

therefore that Navajo ceremonialists be distinguished from shamans by virtue

of their reliance on traditions. Thus, a shaman who no longer alters his

rite on the basis of direct communication with divine

tutelaries, and on the spur of the moment, should be called a priest.

This line of demarcation extends the phenomenon of shamanism just enough to

accommodate the American Indian situation. Since ecstasy is a matter of

degrees and is an inner happening, detection is often very difficult. For

field research in American Indian religions the boundary line that is

suggested by Opler is therefore more useful.

Moreover, since the Tungusic terminus "shaman"

has already been linked to loosely related phenomena elsewhere in the world,

this slight adaptation seems justified.

Page 13

Theologically defined, this means then that a shaman should be

regarded as having become a priestly practitioner when his divine tutelary

(or tutelaries) no longer adds new revelations

to his rite. Therefore, wherever in this book I mention Navajo "shamanism"

or refer to "shamans" I actually have reference to a time when the northern

religious heritage of Apachean hunters was still intact -- a time, perhaps,

before the Spanish name "Navajo" was applied.

Our Coyoteway ceremonialist may thus be

called a practitioner, or else, he may be called a priest. I like the term

"practitioner" because it implies a professional relationship toward

individual clients; I dislike the term because in our Western culture it

generally refers to a materialistically trained, scientific medical doctor.

I like the designation "priest" because it refers to a mediator between

god(s) and humankind; I dislike the term because priests are generally

thought of as mediating between god(s) and organized groups of people.

Navajo singers perform their ceremonials for individual clients. In an

attempt to get the best part of both suggestions I have decided, in this

book, to refer to our ceremonialist primarily as "priestly practitioner." In

order to escape the awkward grammatical consequences of this long title, I

will occasionally substitute such alternatives as healer, practitioner,

priest, singer, and priestly singer.

The primary participants in the Coyoteway

ceremonial, the divine Coyote People and various other divine personages, I

prefer to call "gods." In much of anthropological literature the term

"super-natural(s)" has been adopted. In my opinion this is a most

unfortunate choice. To apply this term in Navajo religion, where nature is

not yet distinguished from a divine realm, would be more distorting than

simply referring to gods as greater-than-human personal powers or Holy

People.

Finally, an explanation is called for concerning the capitalization

of some English nouns in translations of Navajo texts. The practice of

writing ordinary English nouns with small letters, and of capitalizing the

names of persons, is based on a view of the world where the observers

pretend to know, absolutely, the difference between an "object" and a

"person." This practice is a legacy of British Empiricism and the result of

scientific ambitions. But, unlike English orthography, Navajo traditional

thought has none of its roots in this philosophy. Navajo traditionalists are

obviously capable of identifying certain less-than-human entities as

"objects" or as "things," but, when on subsequent occasions some of these

"objects" happen to reveal themselves as persons, then traditionally

oriented Navajo minds remain open also

Page

14

to this possibility. When in addition such entities that are recognized as

persons are seen as being in some ways greater-than-human, they are

approached as Holy People, accordingly, with prayers and with songs. The

least an editor can do in rendering these prayers and songs, and in

describing the Navajo religious posture in English, is to refer to what may

be Holy People by way of capitalized "proper" nouns.

2

Man With Palomino Horse and His Tradition

The Singer and His Teachers

He lives in one of the southern valleys of Black Mesa, approximately five

miles from Pinon. A big man, he stands broader and taller than most of his

fellow tribesmen, even now that he is well advanced in years. Various

estimates of his age, of being somewhere in the eighties, were given by

people who know him. At the time of the ceremonial he himself answered that

he was now seventy-seven years old.

We do not know how soon among his tribesmen our practitioner became known as

Man With Palomino Horse. Presumably he had to be old enough to own an easily

distinguishable horse with a white mane. In those days, we can infer, the

man's horse was more conspicuous than its rider. The people named the rider

after his horse. The horse has long since died, the singer has become an

important person in his own right, but he is still known as the man of that

famous palomino horse. Our singer, who today is known among his fellow

tribesmen as an accomplished practitioner of Coyoteway

and of Lifeway (Female Shooting Branch), and as one who assists in the

performance of various other song ceremonials, must be searched for in

the United States census books under a different name. Man With Palomino

Horse

--

hastiin

bitsiigha' ligaii

hólónii,

of the Coyote Clan

--

seemed an impossible designation to the government official who was given

the difficult task of recording the man's existence. With an unusual flare

of imagination this unknown official assigned him a name not much

Page 16

shorter than the original name would have been: Jessie James Begay the

First.

Man With Palomino Horse said he learned the Coyoteway

ceremonial from Many Whiskers (bidághaa'

lání) who died in the middle fifties. His

former apprentice, Luke Cook, mentioned the maternal uncle of Man With

Palomino Horse, Yellow Hair (tsii'

litsooí), as an intermediary teacher. So it

appears that Yellow Hair was an older apprentice of Many Whiskers while Man

With Palomino Horse was a younger one. When Many Whiskers died, the Man With

Palomino Horse finished learning Coyoteway by

observing Yellow Hair. Many Whiskers, the grandfather who taught Yellow Hair

and Man With Palomino Horse, learned the Coyoteway

ceremonial from another and older grandfather, He Who Returns Angrily (hashkéé

náane), who died when our practitioner was

only six years old-thus around 1903.

When given the name hastiin

neez to identify, the face of Man With

Palomino Horse lit up. Yes, he knew hastiin

neez. From him he has the

sandpaintings that were used in our ceremonial.

This piece of information needs some slight modification, perhaps. Mary

Wheelwright wrote that hastiin

neez, from near Rainbow Bridge, died in 1919. At

that time Man With Palomino Horse was only twenty-two years old. It is quite

possible that he saw hastiin

neez use the

sandpaintings in question. But it should also be taken into account

that in 1929, Many Whiskers gave to Laura Armer

exactly the same sandpaintings. Many Whiskers

was a direct teacher of Man With Palomino Horse until the fifties; so it

would seem natural that our practitioner's knowledge about the

sandpaintings of hastiin

neez was reinforced through him.

Both grandfathers, He Who Returns Angrily and Many Whiskers, were included

when in 1864 Navajo people were deported to the Fort Sumner concentration

camp. According to his age, it is possible that hastiin

neez, who died in 1919, was included also.

This episode of existential fears and hostilities

--

when the Navajos were surrounded by the United States Army, felt threatened

by "Enemy Navajos," Mescaleros,

Comanches, and Kiowas,

and when their number was reduced by famine and epidemics

--

has visibly increased the Navajo awareness of witchcraft. At that time

Evilway rites were primarily called for. Father

Berard (1950, p. 297) reported that at that time

a Chiricahua Apache introduced a sucking cure, which was aimed specifically

against the disease-producing agents of "bean-shooting" witchcraft. This

intensified confrontation could well have contributed some aspects to the

present form of the Coyoteway ceremonial.

Perhaps "Burning the Feathers," the counter-measure for "feather-shooting,"

was added then (cf. note 2, this chapter).

Page 17

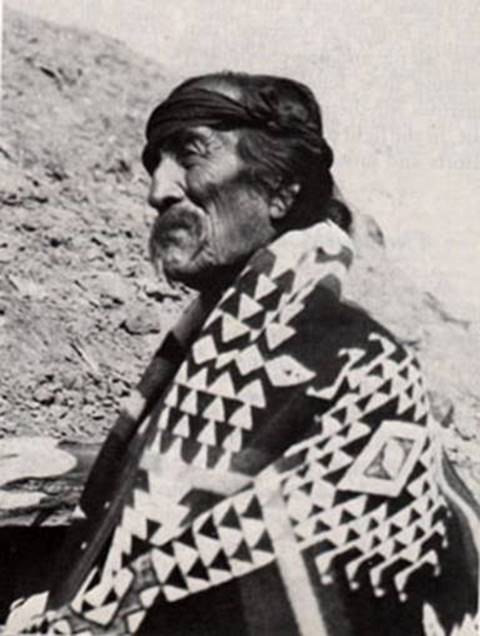

Man With Palomino Horse,

Coyoteway

Hastiin Neez: .

This photograph -- from the Philip

Johnston Collection, in Special Collections, Northern

Arizona University Library -- was identified by Man

With Palomino Horse as his teacher of long ago.

Page 18

Man with Palomino Horse seemed unable to name a still older

Coyoteway singer. However, Luke Cook, who

belongs to the last generation of Coyoteway

apprentices, has heard it spoken that the first

Coyoteway singer who taught the above mentioned grandfathers was

Yellow Man of the Canyon People (tséyi'

niiltsooí). Presumably this man had already

died when the Navajo people were taken to Fort Sumner. All agree,

nevertheless, that Coyoteway was known and had

been performed in Navajoland long before

the Fort Sumner deportation.

Where historical inquiries end, the mythical record usually points a little

farther. Both Coyoteway myths of the

Holyway type (given in Chapters 9 and 10) point

to a place of origin in the La Plata Mountains, in the Mesa Verde vicinity.

Whether Luke Cook's "Yellow Man of the Canyon People" is identical with the

"Nalth-keh-olth-eh"

of tséyi'nii or with the "Grandnephew of

the Coyote-clan chief" of yoo'

hataalii (see Chapters 10, 11), is now

impossible to verify. In any case, what the two myths agree on is that the

Coyoteway ceremonial originated in the Old

Navajoland

--

the place where according to its cosmological orientation one would expect

it to have originated. Old Navajoland is the

place where Navajo-Apachean hunter shamans first seem to have come in

contact with the Pueblo Indian four-directional four-level cosmology and

with the anthropogony of emergence. Courageous shamans that they were, a few

of them ventured down into the hole of emergence from where, according to

the new worldview, all life and power originates. Coyote and fox

tutelaries have been showing their fellow

hunters the right way all along

--

by digging burrows for themselves and by living in the "underworld." Now, at

last, in the light of the Pueblo myth of emergence, could the pioneering

efforts and hints of the Coyote People be fully understood.

The Mythico-historical Origin of

Coyoteway

When Man With Palomino Horse told the story about the origin of

Coyoteway he emphasized that this is the only

story that belonged to the ceremonial from the beginning. He admitted that

some storytellers may have added other Coyote stories, but this story is all

that belongs. Rock-extending-between (Middle Point) is the name of the

place. It snowed early in the morning. A man was going out with the

intention to hunt. He saw Coyote tracks. He started backtracking the Coyote

tracks. They led to a pond that was surrounded with many

Page 19

kinds of green plants. As he approached he saw a ladder sticking out of the

water, barely above the water. On the steps of this ladder the hunter went

down into the water.(1) Down

below he touched ground. It was very beautiful down there. The earth surface

on which we now sit had winter; there was snow on the ground. But below it

was summer; there was green grass, flowers, all over the place. In the east

he saw white buildings. He went over to the buildings and saw Coyote human

beings. They were in fact human beings, but they were Coyote People. There

were lots of young beautiful girls with long and wavy hair. Then he saw all

the fields of corn. The corn was ripe. The Coyote People gathered the corn

and cooked meals for him. He ate and stayed overnight.

Toward evening the Coyote People assembled, and he was taught the

Coyoteway ceremonial

--

the songs, the prayers, the procedures, and the

prayersticks. He was taught everything. He simply learned it from

these people. They told him that the prayers, the songs, and the ceremonial

items are also to be used on the earth; and these are the ways you are going

to use them. These were all read to him. It seems, perhaps, that he wrote it

all on papers of his mind. Then he began climbing up again to this earth. He

came up through the water, on the ladder, to the earth.

So this is the simple story about where the songs and the ceremonial came

from. So this is what it is. This is what my grandfather told me; Many

Whiskers is his name. Further back in time there was another grandfather who

died of old age, his name is He Who Returns Angrily. He died when I was only

six years old. The other grandfather died more recently, about twenty years

ago. So these are the people from whom I have learned it. They taught me

these things, and I accepted them. I learned them. And that is the way it is

today. It is a simple story. And this is all.

_____________________

(1)

The setting of this myth, with "a ladder sticking out of the water," is

identical in all the three available Coyoteway

versions of the Holyway type. The two other

versions by yoo'

hataalii and by tséyi'nii, are

given in Chapters 9-10. A related Lipan Apache story can be found in Morris

E. Opler's Myths and Legends of the Lipan Apache

Indians, 1940, pp. 41-44. The setting in all these myths is obviously

related to Pueblo kiva architecture and to the mythic flood caused by the

Water Serpent (see Luckert 1976). The origin

myth of the Hopi Reed clan appears to have provided the model for

Coyoteway cosmology. The myth of the Hopi Snake

clan, in some of its aspects, may be the prototype for the Reed clan myth.

What is unique in the ecstatic journey of the Navajo shaman can be seen

after subtracting the Hopi elements from the available

Coyoteway myths. The Hopi Reed clan hero went in search of a hunting

animal. From the crest of a mountain he sighted a dog. The animal trotted

ahead of him and led him "to what appeared to be a water hole. Protruding

from the water was the top of a ladder. The dog began to descend the ladder,

and as he did so the water disappeared." Spider Grandmother advised the man

to follow: "...this is the kiva of the dog people." The hero obtained a

hunting dog to take home with him. In the origin myth of the Snake clan the

ancestral hero married a Snake maiden and learned how to perform the Snake

ceremonies(Courlander 1971, pp. 58. 103-5). Thus it appears that the Navajo

Coyoteway myth of the

Holyway type is a blend of Hopi Reed clan cosmology, of something

akin to Hopi Snake clan initiational procedures,

and of Navajo shamanic experience and/or ingenuity.

Page 20

On two occasions we asked Luke Cook about what he knows concerning the

origin of the Coyoteway ceremonial. In the first

instance he referred simply to the mythic age immediately after the

emergence of the first people from the underworld. Everything else in human

history began with First Man, First Woman, First Boy, First Girl, and

Coyote, so why should the Coyoteway ceremonial

not be traceable to these? On the second occasion, while explaining the

Feather-burning Rite, he told us the myth of Coyote's adventure

into Narrow Canyon. When later we asked Man With Palomino Horse specifically

about this myth, he claimed that, while it explains the Feather-burning

Rite, it has nothing to do with Coyoteway;

moreover, it belongs to the Upwardreaching

Chant (hanelnéhe) that serves the primary

purpose of driving away the evil influence of ghosts, witches, and Coyote.

Concerning a first Coyoteway ceremonial on the

rim of Narrow Canyon, about which Luke Cook informed us, our practitioner

seemed to know nothing. Nevertheless, Luke Cook's story is verified by

earlier recordings; it contains important historical data, coming from a

time when the idea of feather-burning was introduced and when

Evilway-type thinking not only pressured but

also shaped the apologetics of the Holyway-type

Coyoteway. There was, in fact, a

Coyoteway ceremonial performed on the rim

of Narrow Canyon. The mischievous Coyote was indeed chased out

of Narrow Canyon, but not, as Evilway singers

maintain, because he was Evil incarnate. Rather, Coyote became a patient

--

thus the prototype of all subsequent patients and healers. Divine Coyote

People came to heal their kinsman. Thus, Coyote is not the evil being which,

according to Evilway mythology, only deserves to

be driven away. Coyote is a person; more yet, Coyote is a Navajo.

The Coyoteway originated at Narrow Canyon (tséyi'

haats'ósí). The Bird People lived in this

canyon under ledges along the cliffs. Coyote ventured among them and angered

them. In revenge the Bird People shot their feathers into Coyote. They were

using these feathers as witchcraft arrows

--

shooting them like feathered arrows. Coyote barely escaped to the top of the

canyon. He felt miserable.(2)

______________________________

(2)

According to a Taos tale (Parsons 1940, pp. 112-15), Coyote became

envious of clothing that White-headed Eagles possessed. They agreed to trade

some of their clothing if Coyote would get for them a blue coyote fur. To

accomplish his end Coyote plays dead while all kinds of coyotes examine his

condition -- Red Coyote, Gray Coyote, Black Coyote, and Blue Coyote. In the

process Coyote kills Blue Coyote, skins him, and trades the fur for the

Eagles' clothes.... Up to this point-if we assume Navajo borrowing from

Pueblo mythology-this story explains perhaps the curious fact of why in

Coyoteway coyotes are constantly mentioned and

why the skin of a "blue coyote" (gray fox) and a stuffed "blue coyote" are

actually used. The Taos tale continues: ...Encouraged by his improved

appearance, Coyote challenges the Eagles to a fight; this time around his

personal clothing, his own skin, is to be at stake. In the course of the

fight the powerful Eagles shoot

"very little, fine arrows" into Coyote. Coyote is defeated and loses his

skin. This "feather-shooting"

episode seems to extend the mythological Pueblo influence to the Navajo

Evilway Upwardreaching

ceremonial -- eventually even to the present Evilway

intrusion of Coyoteway itself. Coyote's

association with witchcraft seems

otherwise well documented in the Pueblo realm. Parsons informs us that

"most Pueblowitch transformations are into

Coyote" and that frequently in mythology Coyote is also regarded as the

First Witch (Parsons, 1939, pp. 217, 1067n). In addition, a "Feather-burning

Rite" has been reported from Zuni (Ladd 1960, p. 118)

Page 21

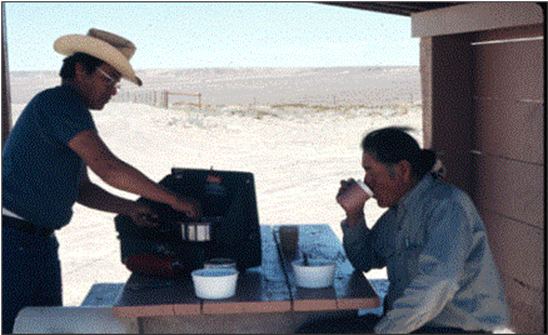

Luke Cook on horseback, with Mrs. Cook and son,

on the day of the author's first visit to his homestead, in 1971.

In May of 1973 we made another

attempt to reach the singer (see Preface).

Johnny

and his father Luke, preparing lunch at a roadside-stop near Second Mesa.

Page 22

Then Coyote came to the home of Horned Toad and there he asked for food. He

demanded to be given all the available food. Horned Toad refused. Thereupon

Coyote became angry and swallowed him. He thought he had killed him. And

Coyote sat in Horned Toad's house, his hogan.

Shshd! Coyote heard a sound and concluded that

he was in a ch'íídii

hooghan; he was feeling increasingly worse.

(The humorous implication is what every child knows: if Coyote had actually

killed Horned Toad and had dispatched his ghost, the

hogan would indeed be hok'ee

--

a ghost hogan. The ghost of Horned Toad would

naturally claim the home in which he was dispatched.) Meanwhile, Horned Toad

who was still alive crawled all around in Coyote's belly, exploring it. He

wondered what all the different organs were and grabbed them as he

investigated

--

stomach, lungs, and the heart. At last he pinched off the heart and came out

through the mouth. There was blood in the mouth and face of Coyote, stemming

from his internal bleeding. For the time being Horned Toad had killed Coyote.(3)

At this point the narrator broke off, but from subsequent conversations it

became obvious that because of his self-provoked sufferings, because of his

"coyoteing around," Coyote has himself become the first

Coyoteway patient. This happened up on the rim of Narrow Canyon where

other Coyote People had gathered to revive him. This conclusion of the myth

transforms a potential Evilway myth into one of

the Holyway type. Coyote does not remain the

epitome of Evil;

rather, he becomes the prototype of all subsequent

Coyoteway patients and healers. According to the ancient way of

Coyote all subsequent sufferers

--

though they may have brought their suffering upon themselves through

"coyoteing around"

--

are given a chance for recovery. Divine grace and participation abounds over

merit.

___________________________________

(2)

A related myth is given in the narrative by tséyi'nii (Chapter

10, paragraphs 21-28). See also the introductory statement to this myth.

____________________________

PART TWO –

COYOTEWAY PERFORMED

Pages 25

3

The Nine-Night Sequence

The nine-night Coyoteway ceremonial divides

naturally into two four-night portions and a one-night summary. Each of the

four-night portions is further divisible into an evening and a morning

section. This enables us to discuss the ceremonial as five groups of

ceremonies: Unraveling Ceremonies, Fire Ceremonies, Basket-Drum Ceremonies,

Sandpainting Ceremonies, and the Ninth-Night

Summary.

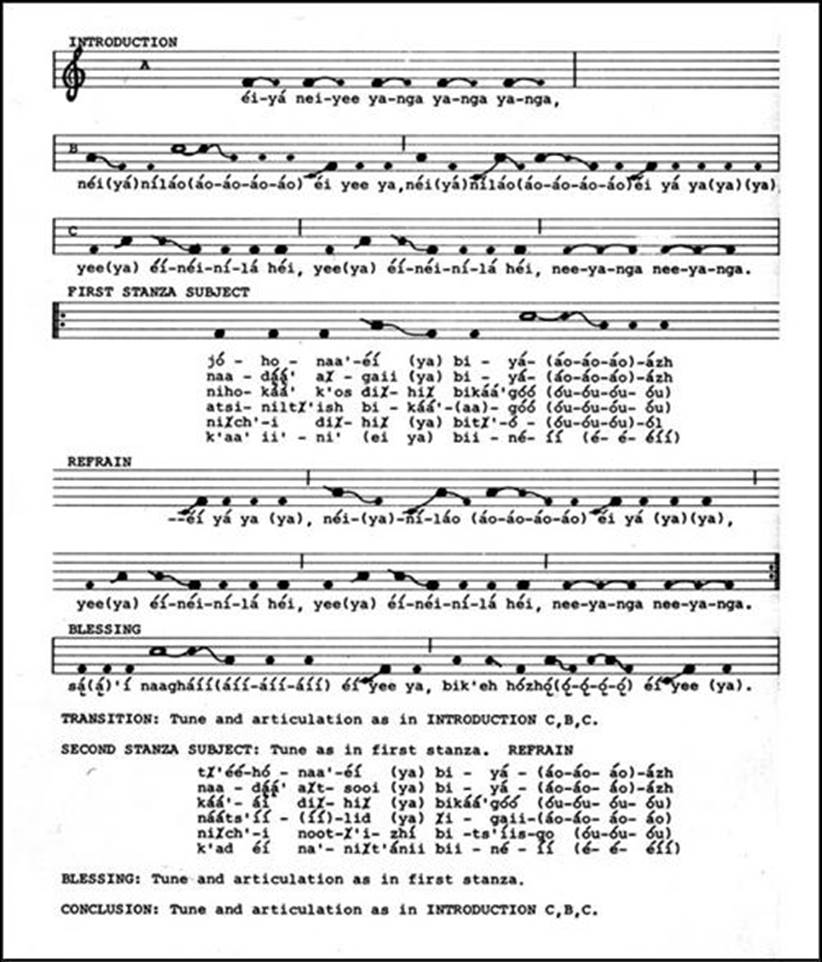

During the nine-night sequence of the Coyoteway

ceremonial many songs are chanted. All have been recorded on tape and are

presented here in the form of a free English translation. Johnny Cooke

usually dictated to me from the tapes, sentence by sentence, what he

considered to be the best English translation. Sentence by sentence, in

return, I suggested alternate formulations by utilizing the largest possible

number of synonyms. In addition, Johnny Cooke frequently explained different

contexts in which certain Navajo expressions are used. Whenever we were in

doubt about a particular word or phrase, we took it to Luke Cook or to Man

With Palomino Horse to have it explained. In the end, the task of editing

and balancing the lines fell on me. While it would be foolish to insist that

every word in these songs is translated with unambiguous precision, both

Johnny Cooke and I are satisfied that we have done what honestly could be

done with this difficult archaic material. For the specialist there will

always be copies of tapes that we deposited at the Navajo Tribal Museum,

Window Rock, at the Museum of Navaho Ceremonial Art, Santa Fe, at

For presenting the entire ceremonial as an illustrated documentary,

it has seemed best to group the various ceremonies together with their

repetitions from subsequent days. So, for instance, the Unraveling

Ceremonies of the first four evenings are discussed as one unit, regardless

of there having been Fire Ceremonies on the

mornings between. Combining repetitions into a single discussion makes for

easier reading and comprehension; however, it interrupts the actual

recording sequence. In order to remedy this difficulty and to facilitate

easy checking on the actual song and prayer sequence, a continuously

numbered index is here provided. Numbers in parentheses indicate earlier

occasions in the sequence where the same song has been chanted.

The Nine-Night Sequence of Coyoteway

Evening and Night Morning and Noon

1. Unraveling Ceremony Fire Ceremony

2. Unraveling Ceremony Fire Ceremony

3. Unraveling Ceremony Fire Ceremony

4. Unraveling Ceremony Fire Ceremony

5. Basket-drum Ceremony Sandpainting

Ceremony,

One-yé'ii

6. Basket-drum Ceremony Sandpainting

Ceremony,

One-yé'ii

7. Basket-drum Ceremony Sandpainting

Ceremony,

One-yé'ii

8. Basket-drum Ceremony Sandpainting

Ceremony,

Three-yé'ii

9. Basket-drum Ceremony

Summary

Index to Song and Prayer Sequence of Coyoteway

First Evening

1. They were given 2. Now it has begun moving

3. With these he is well again 4. By these he was led

5. Hwii eiya

eiya! The sound was heard

First Morning

6. By sternness, whatever your name is 7. I bring these to you

8. Formal Prayer 9. He has walked

10. This is the Fur 11. The Red Berry Shrubs

12. It is his Water 13. He who was given

14. The Red Berry Shrubs (cont.) 15. The Furs are put in the water

Second Evening

16. The stick stands upright 17. With these he is well again (3)

18. With these he walked 19. With these he ran

20. By these he was led (4) 21. The sound was heard (5)

Second Morning

22. I bring these to you (7) 23. Formal Prayer

24. He has walked (9) 25. This is the Hogan

26. On these he walked 27. The Medicine is being made

28. The Medicine is ready 29. The Medicine I ate

30. The furs are put in the water (15)

Third Evening

31. He brought it back 32. Now it has begun moving (2)

33. With these he is well again (3, 17) 34. With these he walked (18)

35. By these he was led (4, 20) 36. The sound was heard (5, 21)

Third Morning

37. I bring these to you (7, 22) 38. Formal Prayer

39. He has walked (9, 24) 40. With these he walked out again

41. He is walking in the water 42. With these it is coming out